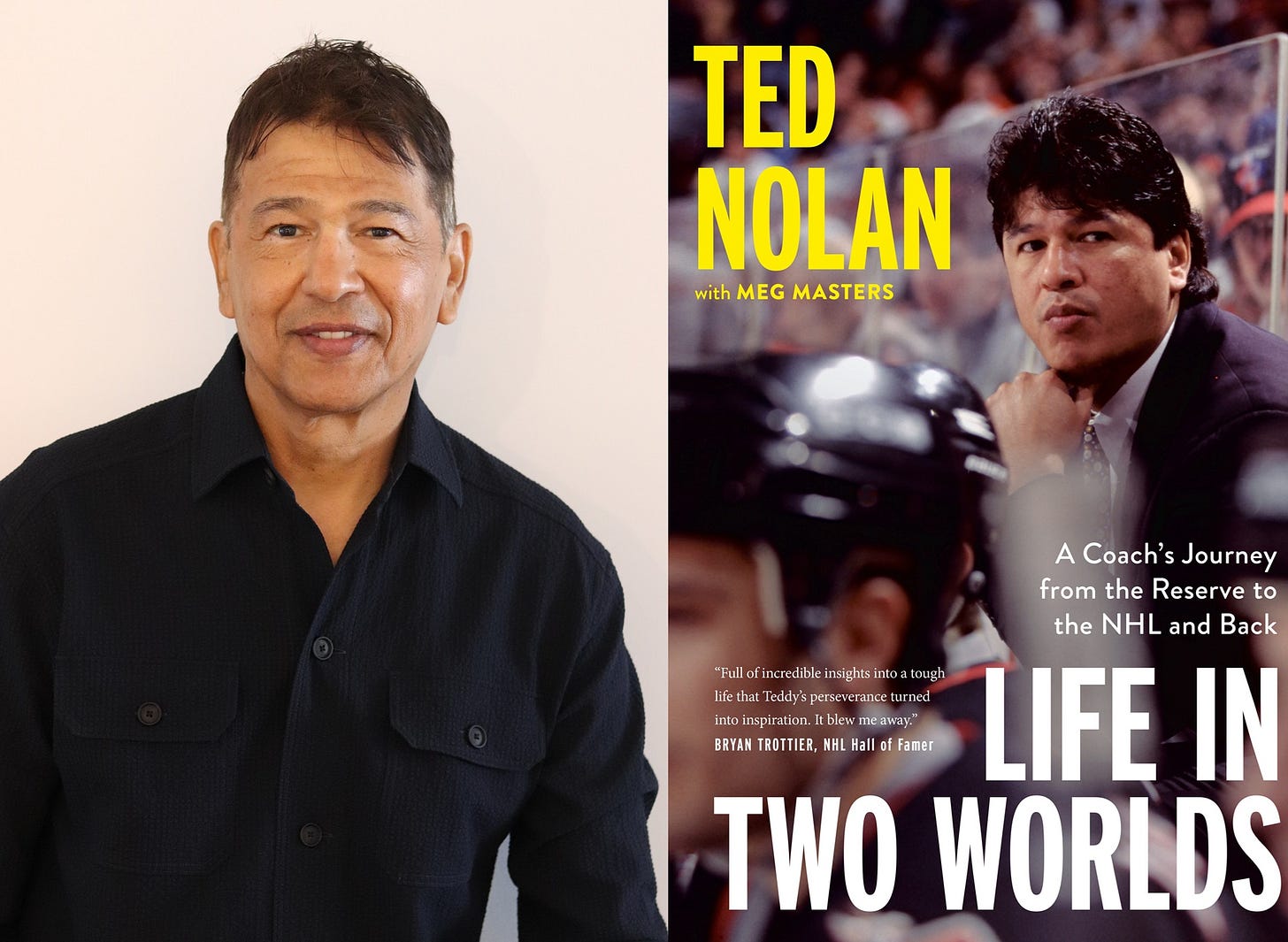

Ted Nolan talks "Life in Two Worlds: A Coach's Journey from the Reserve to the NHL and Back." (SportsLit S7E07)

A listening guide to our pod 'sode with the National Aboriginal Achievement Award and NHL coach of the year winner about his long-awaited memoir about hockey and his Ojibwe identity.

Ted Nolan was sharing a happy memory when he made a turn toward his ongoing battle with cancer.

In his memoir, Life In Two Worlds: A Coach’s Journey from the Reserve to the NHL and Back (with Meg Masters, Viking/Penguin Random House Canada, Oct. 10, 2023), Nolan mentions his fondness for the cult-classic action drama Billy Jack. As a fellow fan of the 1971 indie picture, I had to ask about it,

“Billy Jack was a childhood hero to me, even though he was a fictional character,” Nolan says in Neil Acharya and I’s most recent SportsLit episode. “I actually just bought a Billy Jack hat. I’m not sure if you’re aware, but I came down with multiple myeloma about six months ago, and that last round of (chemotherapy) took out all my hair. My grandson said, ‘Papa, you need a hat,’ so I went out and got myself a Billy Jack hat.

“Knock on wood, I’m feeling a little stronger,” Nolan added in response to Acharya’s follow-up question. “They’re my new heroes, the people who go through this terrible disease, along with the doctors and nurses. I had the last chemo a month and a half, two months ago, and I’m just now starting to feel like myself.”

Our hour-plus of conservation with Nolan ranged across his sporting life and his activist and advocacy work for Indigenous people in higher education and sports. Growing up in Garden River First Nation, or Ketegaunseebee, Nolan lived among residential school survivors and others who had bowed to what he calls “despair.” He has worked to foster opportunities. Since the early 2000s, the former NHL and Olympic coach has had a foundation, named after his late mother Rose Nolan, that presents scholarships to First Nations women.

It is a universal truth that more equitable outcomes in education create a fairer society. Another plain-and-simple fact is we have to keep working in Canada so education systems and sports structures created in a colonial system no longer reflect that.

There is some heavy subject matter in the book and podcast episode, but some fun too. Along with querying about Billy Jack, and a windmilling wunderkind named Darren Zack, the other hyperspecific self-indulgent question I had for Ted Nolan was, “who is your favorite Jim in Shoresy?”1

Did I slip that through the five-hole of time constraints? Press play below to find out.

A link to buy the guest’s book is available through sportslit.ca. Here are some notes that might add context to the conversation.

Intro

0:30-8:30. In this section, Neil and I relay how Nolan described his formative years. It is evident that Nolan felt loved and protected in his large family of 12 children, but there was also a “scarcity” of material resources and indifference from white society.

There are some gut-punching passages. Nolan relates how his teen self stuck it out while he faced horrid racism and culture shock during his first season of Junior A in Kenora, Ont., in the mid-1970s.

“My resistance to leaving was about more than my own future,” is how Nolan phrases it in the book.

“ … Staying on in Kenora, refusing to quit even if I wasn’t wanted, that was an act of defiance and a chance to show that we could succeed in the outside world, even if things were stacked against us.”

8:30-12.45. We cover background on Nolan’s playing career and his coaching tenure with the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds. The ’Hounds won back-to-back Ontario league (OHL) titles in 1991 and ’92. In ’93, they won a special series against the Peterborough Petes to earn the host berth for the Memorial Cup tournament, which they won.2

12:45-19:00. “He’s not into playing any games, for better or worse.” As a hockey journo, Neil poked into what affected Nolan’s fortunes working in the NHL. It still seems gobsmacking that an NHL coach of the year could wait eight seasons for his next good opportunity, which came in 2005-06 when he guided the Moncton Wildcats to the Québec league title. That success led to a two-season run as head coach of the New York Islanders.

19:00-21:20. Besides the movies and Gary Smith long-form feature I mentioned, it is also well worth reading Brandi Morin’s Our Voice Of Fire — and anything by Waubgeshig Rice.

Interview

21:20-27:15. “Those days (of keeping it all inside) are over and they should have never been.” Right off the hop, Nolan explains how much hurt he internalized became apparent in 2020, in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd, and the allyship and activism among Indigenous people.

27:15-39:00. “When I went to Kenora, that was the first real test.” In the book, Nolan describes how one of his older brothers was a member of the American Indian Movement, a civil rights organization that was prominent in the 1970s. Nolan met AIM leaders as a young teen, around age 13 or 14. That helped with building the inner strength he needed when he went off at age 17 to play for the Kenora Muskies in the Manitoba Junior Hockey League.3

39:00-42:30. Nolan touches on developing a radar for subtle or surreptitious racism out in the hockey industry.

Ted Lindsay (1925-2019), the Hockey Hall of Fame left wing and Gordie Howe linemate, was general manager of the Detroit Red Wings when Nolan was a 20-year-old rookie in 1978. Lindsay led the first attempt to establish a players’ association in the NHL in the 1950s. The Red Wings retaliated by shipping Lindsay to the league’s weakest team, Chicago, sabotaging their club to make a point. Detroit, which had won four Stanley Cups in six seasons in the 1950s, would not win it again until 1997.

Lindsay was portrayed by Aidan Devine in the 1995 television movie adaptation of Net Worth. Well worth seeing.

42:30-49:30. “I wish our people would have had a chance to say ‘no.’ ” There was some irony for Nolan when, as the Soo Greyhounds coach, they pitched 16-year-old Eric Lindros on coming north as the No. 1 overall choice in the OHL priority selection draft.

Lindros’s refusal to go to the Soo led to the OHL developing its defected player rule. Teams were given a 10-day window in January to trade a first-round selection who had not reported. The Oshawa Generals won the 1990 Lindros sweepstakes and went on to win the OHL title and Memorial Cup. But the Soo beat them in the ’91 OHL final.

We mention some guys. For anyone who doesn’t remember early 1990s OHL rosters off-hand, Rick Kowalsky, who was captain of Nolan’s 1993 Memorial Cup-winning team, is now coach of the American league’s Bridgeport Islanders. Chris Simon played under Nolan for one season in the Soo before playing 960 games in the NHL and KHL; the rugged winger won the Stanley Cup with Colorado in 1996 — at the expense of the Florida Panthers and recent guest Doug MacLean.

49:30-1:00:00. “Tried to get him to talk about it, and he refused.” The public may never know the true source of the beef Dominik Hašek had with Nolan in ’97.

This section covers the tumult from each stint Nolan had with the Buffalo Sabres (1995-97, 2013-15).

1:00:00-1:07:00.“I went through sweat lodges, I talked to some mental health people, and I finally got it out of my system.” Nolan describes the emotional labour it took for him to accept his fortunes in Buffalo. He did not coach full-time for eight seasons until he got an offer from Moncton in 2005-06.

Brad Marchand, current captain of the Boston Bruins, was a 17-year-old forward that year in Moncton. Keith Yandle came north out of the Boston area to serve as a cornerstone defenceman, before moving on to play over 1,100 games in the NHL.

1:07:00-1:14:00. Some background on some of my picayune questions. Nolan has coached a women’s team from Wiikwemkoong First Nation in national aboriginal hockey tournaments. And yes, there are 28 “long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserves” as of the last update on Aug. 21, 2023.

Also, the Darren Zack question was a shot in the dark. Zack is an absolute legend in that underhanded diamond demimonde.

1:14:00-FIN. This is the bridge in Garden River First Nation where Jordan Nolan brought the Stanley Cup.

That is more than enough for now. Please stay safe, and be kind.

By process of elimination, it would have to be Jon Mirasty, eh? A parent can’t play favorites between their children. Nolan’s sons, Brandon Nolan and Jordan Nolan, play the other two-thirds of a same-named trio of rugged forwards in Jared Keeso’s hockey-based comedy series. That’s the joke.

Their introduction is probably my favorite YouTube clip from Shoresy. Another contender is Shoresy chirping an opponent during a pregame warmup (“SCHNURR!”).

My maternal grandfather, John Clarence Head (1922-1993), did save a poster of that Greyhounds team for me. His energy returned to the earth just days after the ’Hounds won the Memorial Cup on home ice.

Kenora was part of the Manitoba junior league from 1968-82. Alumni include Charlie Simmer, who once had a 56-goal campaign with the Los Angeles Kings. The northwestern Ontario city is back in the Junior A game these days. The Kenora Islanders are a member of the Superior International Junior Hockey League, which is spread across northwestern Ontario, with one team located in Superior, Wisconsin.