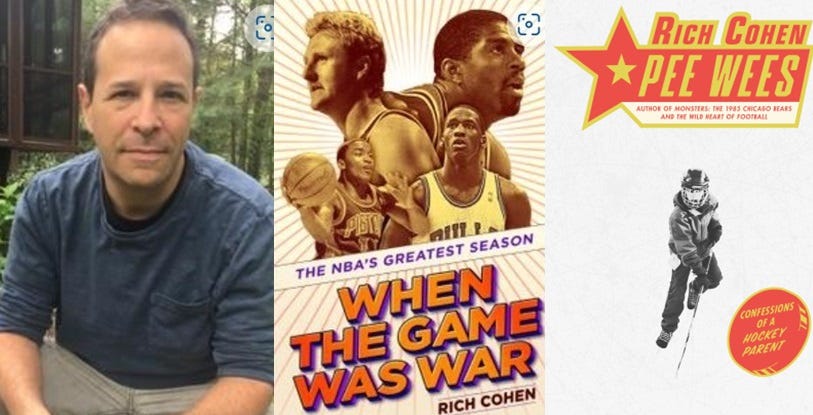

Rich Cohen, 'When The Game Was War: The NBA's Greatest Season' (SportsLit S7E8)

Second-time guest Rich Cohen discusses his new book that evokes when the NBA was "Game of Thrones on the hardcourt" and soft takes were not allowed. (Plus some afterword on life after Substack.)

It seems as if Rich Cohen digs out from the heart of the matter, rather than drilling down to it.

One strain that runs through Cohen’s deep body of word-working is that he starts with a thought or an emotion, a nettle poking at him, and then explores it. That can be a sport, the colorful history of his family, or the music of the Rolling Stones.

The discovery that Cohen was ‘had next’ with his new book, When The Game Was War: The NBA’s Greatest Season (Random House, September 2023) piqued curiosity as SportsLit fodder for Neil Acharya and me. The NBA of the 1980s has been a fecund period for authors, filmmakers, hagiographers, marketers, and myth-makers. What new angles could there be about the decade where, as Charles Pierce once put it, basketball became the “premier athletic show” in North America, before conquering the world?

For Cohen, the launch point seems to be the psychic hold the 1987-88 drama in the National Basketball Association had on him from what amounts to two-thirds of his lifetime. He builds out that sentiment of ‘The ’87-88 Season Was The Best, Change My Mind’ by pointing out the 1988-vintage NBA had four dynasties fronted by talismanic stars. On the coasts, two were fighting to stay on top — the Larry Bird-led Boston Celtics and Magic Johnson-led Los Angeles Lakers. In the Midwest, two were ascending — the Isiah Thomas-driven Detroit Pistons and the Chicago Bulls powered by Michael Jordan (and Scottie Pippen). The best team might not have won the C’hip.

“It was kind of like the history of empires in Europe during the Thirty Years War,” Cohen tells us. “I always compare it to Game of Thrones on the hardcourt, because you don’t know who is going to be the hero in the end.

“What I try to do is recover these games as narratives, and that is my ongoing battle against over-highlighting,” Cohen adds later in our talk.

Cohen explained how, at a time when creating and professional writing is imperiled by AI, putting the words together still matters. Neil also got him to open up on how he writes and writes until he gets the gold, and why that still matters in a world where AI is a treat to every last little spark of creative madness.

“Good writing is alive — it just holds you to the page,” Cohen adds. “It’s like the page is shimmering. It sounds crazy. It’s something that can put into words what was a half-formed thought … good writing causes you to see something you’ve always seen, in a new way.”

The ultimate compliment pro athletes have for their peers is that they would pay to watch them play. Word nerds might apply that to Rich Cohen — I would pay to watch him write, knowing the writer’s life is solitary.

Cohen was with us before in 2021, discussing Pee Wees: Confession of a Hockey Parent (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, January 2021).

Intro

1:00 Neil posits that the book is a response to The Last Dance docuseries that covered the final season of the Chicago Bulls dynasty a decade hence in 1997-98. To refresh, the “Jordanaires” had two championship three-peats sandwiched around Michael Jordan trying to play baseball. In 1987-88, though, Jordan was a fourth-year individual star, and Scottie Pippen was a rookie.

4:35 The reference to Isiah Thomas growing up “poor as poor” in Chicago comes from Zeke himself in a 2020 interview with Shannon Sharpe.

7:45. What, no one remembers the ’87-88 season? The rim-rattling dunks of Dominique Wilkins? The cagey rebounding of Michael Cage? The indomitable will of Isiah Thomas? Ah, man! For more information on that season, consult Basketball-Reference.com! Okay, fine, some refreshers.

Cohen writes that the NBA of 1988 was “what America wanted to be — fast, athletic diverse.” That appealed to the kids, teens, young adults, and, of course, shoe companies. A decade earlier, baseball players got most off the national commercials. By ’88 or 1989, basketball players were the most marketable American sportspeople, save for Bo Jackson and the top NFL quarterbacks.

It seemed pertinent to remind listeners of how differently the game was played in 1987-88 vis-à-vis 2023-24. The apt phrase that Rich uses is that “the logic of the three” has “deforested the interior.” You could while away an afternoon looking at how physical the sport was in the ’80s.

The NBA added the three-point shot in ’79-80. There was still an aversion to the long-range game. It was not the national rule in men’s college basketball until 1987-88; individual conferences could decide whether to have the three.

It took until ’87-88 for NBA teams to average five triple attempts per game. Seventy-three current players now take that many, and more than a dozen players in the 12-team WNBA did so last season.1

To illustrate, here are the long-term trends with team points per game, attempted twos, attempted threes, and shooting percentages in the NBA each season since 1976. Teams do not necessarily attempt more shots than their counterparts of nearly a half-century ago. The force multiplier is the three-pointer evolving into a first option, which started to spike in the 2010s.

The trend lines across the 27-season run of the WNBA are similar. Early ‘W’ teams played in the high 60s to low 70s. They know play in the 80s. Teams try about double the amount of threes as their 1990s counterparts, but they don’t necessarily make them at a noticeably greater rate.2

In this section, I mention Bird and the Celtics having the best “shooting success rate” of any ’87-88 team. That was a synonym for effective field goal percentage (eFG%). That stat accurately reflects shooting production, giving 50 percent more weight to a three-pointer than a two-point basket — because math.3 The code has been cracked, which doesn’t necessarily pose a problem for the NBA, yet…4

Stuff your stats in a sack, nerd. Get to Rich Cohen.

Interview

14:40 “What I didn’t like about what had happened to Isiah and the Pistons as a Bulls fan from Chicago.” Remember, Chicago lost to Detroit in the NBA playoffs thrice in success (second round 1988, conference finals in ’89 and ’90). The Bulls swept the Pistons in the 1991 Eastern final, before going on to their first title.

Michael Jordan and Isiah Thomas had beef, in the parlance of our time. They were too much alike. But hell, here is the “ankle game” from Game 6 in the 1988 Finals between the Pistons and Lakers.

The Dennis Rodman-Scottie Pippen play that Cohen references occurred during the 1991 Bulls sweep. The play has 1.3 million views, but comments are disabled.

22:40 If this segment achieves anything, it was sending #PleaseLikeMySport to a well-deserved death. Everyone has seen the dog-whistly memes glorifying the toughness of hockey players versus the supposed softness of basketball. It has never been true. A basketball floor is hard, man!

“There was something great, about a model of how to live your life, about the guy who would overcome getting beat up,” Cohen says. “There was the satisfaction of overcoming the schoolyard bully.”

We are going to need more retro basketball clips. In recounting the magnetism of the ’88 playoffs, Cohen alludes to the Bird-Wilkins Game 7 duel in an Atlanta Hawks-Boston series.

The great sportswriter Steve Rushin, who is two years older than Cohen, has shared his memory of this contest. As a Bird guy, 21-year-old Rushin was unable to un-transfix himself from a hotel room TV in Milwaukee while Bird was “pathologically unable to throw the ball anywhere but in the basket.” Finally, he had to leave … since it was his graduation ceremony from Marquette University that day.

31:25 Time for a reading. Cohen relates how he examined his own possible “belatedness” bias and the “dangers of nostalgia” that he confronted before embarking on this book. Across 79 interviews, though, there was support for his case for ’88.

39:15 “Detroit was a perfect team for Detroit. And the Lakers, what team is more Hollywood than that?” This section gets into the stakes that fans were wired into this era. And, of course, the four dynasties examined in this book all played in arenas that are long gone:

The Bulls and the ’Hawks hockey team shared Chicago Stadium (1929-1994), AKA The Madhouse on Madison.

The Celtics and Bruins shared the built-for-boxing Boston Garden (1928-1995).

The Lakers and Kings shared the Forum (1967-2001 as a sports venue; still open).

The Pistons played in a football stadium, the Silverdome (1975-2017).

Was it ideal for basketball? Not really.

Chicago Stadium had closed by the time the Toronto Raptors first hooped in 1995, but its dot on the map in a Toronto-oriented fan’s consciousness came through hockey. The Leafs and ’Hawks were in the same division during the 1980s and most of the ’90s. The crushing moment Neil refers to was in April 1989 when Troy Murray stole the puck from Todd Gill to score a goal that put Chicago in the playoffs and ousted the Leafs. That was also the final shift that Börje Salming played for Toronto.

In the moment, there was some sweet schadenfreude in 1994 when the Leafs closed out a playoff series in the last NHL game in the Stadium.5 But the rivalry had cooled by the time Toronto was switched to the Eastern Conference in ’98.

47:00 “What I try to do is recover these games as narratives, and that is my ongoing battle against over-highlighting.” Cohen takes it to the hoop with how we used to take in sports before every single piece of it was monetized.

Cohen references basketball in Lithuania as well as the work of his friend, Seth Davis of The Athletic and CBS Sports. The book by Davis that I mentioned is When March Went Mad: The Game That Transformed Basketball (Times Books, 2009). It follows Bird and Magic’s collision course to the 1979 NCAA final between their Indiana State and Michigan State teams.

55:00 The virtues of irrationality! Cohen mentions two moments that had stickiness for the antiheroes in the Jordan mythology, Thomas and Pippen.

In ’87, the Pistons should have dethroned the Celtics in the Eastern Conference final. To do so, Detroit needed to wrest one win in Boston Garden. They were five seconds from doing the needed deed when Bird stole Thomas’s pass to set up the winning basket in Game 5.

Seven years later, while Jordan was on his baseball sojourn that was not a cover story for a gambling-related suspension,6 Pippen assumed the leadership mantle with a Pretty, Pretty, Pretty, Pretty Good 1994 Bulls team. Chicago went up against the New York Knicks in a second-round series.

In the third game, Pippen refused to reenter after a buzzer-shot play was designed for first-year Bull Toni Kukoc. Kukoc made the shot, and Pippen’s attempt on Chicago’s penultimate possession had barely grazed the side of the barn door.

“Dignity and grace are overrated,” Cohen says; amen to that. However, after the chat, I went a-deep-divin’, and Mr. Al Geaux-Rhythm reminded me that Toni Kukoc was A Problem in the endgame — six-foot-10, lefthanded, and cocksure with the catch-and-shoot. The inbounds play the Bulls ran for Kukoc against the Knicks was pretty much the same as one he converted into a game-winning banked triple against Indiana on Jan. 21, 1994. Guess who inbounded? Scottie Pippen. But, honestly, I only became aware of this last night.

1:01:00 “It was a fight under the basket for control … and we remember that basketball was a contact sport. The team that wins is the team that can take more is the one who wins. And that part of the game has been devalued.” This section deals with the NBA’s Big Shift in shot selection that has accelerated over the last dozen or so seasons, as illustrated in those line graphs earlier in this post. Cohen gets into the value of “grit” versus skills.

Things have changed, that’s all.

I joke here that “my high school was responsible” for it. Crois-moi, tror dig mig, I had a good seat for the Rise of the Great Threequalizer back in the ’90s: my spot on the bench for the Ernestown Eagles.7

If you want to see the best of grit and the new hoops math, go watch the Carleton Ravensteams in March at the U Sports basketball championships. That holds even though Dave Smart is coaching in the Big 12.

While I was a teenage benchwarmer, Dave Smart was in that corner of southeastern Ontario, coaching his Guardsmen club teams. Dave was way ahead at teaching that the offensive game is predicated on post scoring and knocking down those open looks at three-pointers — all while being tougher than a starving dog on a bone.

Tom Turnbull, whose son Stu Turnbull became an all-Canadian guard in the second half of the first decade of the Carleton Ravens dynasty, coached both senior teams at Ernestown at that time. Our rural school did not have a large enrolment, and I do not recall many classmates over 6-foot-5 walking through the door of the gym.8 The value of embracing the three-pointer would have made sense to “T.” So Ernestown had shooters who were reliable from 20 feet out, behind the arc, before any of Dave’s nephews or nieces were wearin’ Eagle green.

So yeah, my basketball immersion imparted that the ‘live by the three, die by the three’ cliché was wrongheaded before it became the received wisdom. Relying on low-percentage and/or forced-up shots is death. Why consciously limit your team’s capacity to outscore the opponent in an offensive game? Of course, I had the benefit of being a blank slate. I never saw high-level basketball without a three-point line. And, being Canadian and an outsider by nature, of course, I was a sucker for anything that went against the status quo.

1:08:15 We close out with some reflections about the value of reading. The great Dan Jenkins was wont to say, “The dumber the world gets, the more the words matter.”

And that does it for Season 7 of SportsLit! Hope we passed the audition!

AFTERWORD

So, you might have already read that Substack’s founders have said they are fine with Nazis publishing and making money on their platform. The letter this athletics supporter signed on to even rated coverage in The New York Times. Either our message had power or there was nothing fit to print that day about the fallout from the latest bun fight that has just riven Ivy League campuses.

A response is better than no response, one supposes. The response is bullflop on its face. Per Ken White, “Flies don’t stop coming into the house because you want them to; they stop because you get off the couch and close the screen door. Any social media or blogging platform faces this. Substack may attract more Nazis than average because Substack has an ‘okay you don’t agree with me now but what if I wrote another 8,000 words about it’ vibe.”

There is some organization to move to another writing platform with minimal disruption to you, Reader. Short version: I’ll go where Craig Calcaterra does, and you will keep getting these posts in your inbox.

Basketball-Reference.com; through games of Dec. 27.

A WNBA game is 40 minutes long, compared to the NBA’s 48.

Subtract a team’s total of successful free throws from their tally. Divide that by two, then divide by total field goal attempts to determine their eFG%.

BasketNews, “Unfortunately NBA Teams Have Solved Basketball…,” Nov. 29, 2023.

April 28, 1994. Félix Potvin backstopped a 1-0 shutout, subsisting off a first-period power-play goal by Hockey Hall of Fame wing Mike Gartner.

Or so Bill Simmons would have you believe. I never bought into the conspiracism.

It was evident in 1993 that Jordan was battling burnout, and then the murder of his father prompted him to do some seeking. As a reader, my frame of reference was Wayne Gretzky. He had asked out of Edmonton at age 27 after four Stanley Cup victories in five seasons, with two best-on-best tournaments included in that span. For Jordan at the start of his 30s, baseball offered a new world to conquer.

Averaged 0.3 points and 1.9 rebounds per game. True story.

Nate Doornekamp, who was a legit 7-footer who played for Boston College from 2001 till 2005, enrolled at Ernestown in 1996, two months after I graduated.

Excellent post Neate, a lot of labour in the name of love of lit!