Kurtis Rourke, 9-win Indiana & Football Influencers | GRUFF, Vol. 3A

Michigan State, alma mater of a favourite author who offered immersion into football, was a great place for my first college football game. And it also connected to some Folklorin' Football Theory.

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Section 3, Row 30 in the south end zone was opposite where nine-win Indiana and Kurtis Rourke found close to peak form. That worked out well since I am a nerd who goes to football games with a pair of binoculars.

When you get end-zone seats in a goals-based sport, you joke about that. Pay XX dollars for a ticket and, sure enough, all the goals, touchdowns, or emphatic dunks happen at the far end, and then bupkes when the teams change directions.

Hey, tickets to sports events are not cheap, plus there is our whole North American culture of instant gratification that we need to unwire and rewire. However, it is a self-check on prefab expectations and being open-minded. The unprecedented is really just something that is right on time — when it comes in good faith.

Having the touchdowns happen at the other end was a blessing in disguise. Decades of football video gaming trains the eyes for that view from behind the offense. Plenty has been written about the effects playing Madden or EA Sports NCAA Football has had on how football is played and watched. There is going to be a biopic of John Madden.

It was handy for my first visit to the American college football experience. It involved watching the Indiana Hoosiers, quarterbacked by Kurtis Rourke, of Canada, and Oakville, Ont., the beat Michigan State Spartans on a perfect fall afternoon for football. The Hoosiers’ rout came in the same city that U.S. Vice-President Kamala Harris made in her push for the Democratic Party ticket to carry Michigan and earn an Electoral College victory. Take those simply as time stamps.

Please, subscribe; subscribe, please

Hello, if this sort of outsider, recovery-focused, mentally healthful sportswriting appeals to you, please consider a free subscription. It feels needy to ask, but a ‘new free subscriber at neatefreaksports!’ notification is a positive.

The reason for asking is that organic reach has been obsoleted by how much the other socials are throttling down on ‘linking out’ for creatives. About 82 percent of reads are from subscribers. So, more people getting it in their email inbox is a win-win-win.

Did someone need to know the Indiana quarterback is from Canada to enjoy going to the game? ’Course not. Two Indiana fans were seated in front of us, and they did not know. An explanation that Oakville is “between Toronto and Hamilton” did not register, but “an hour and a half north of Buffalo” twigged an ohhhhh of recognition.

Indiana has never been 9-0. A woman of colour has never led a party to victory in a national election in the United States, America, Canada, or the United Kingdom. There has, feel safe in saying, never been a born-and-raised Canadian this high in the NCAA passing efficiency rankings.1 And there is a whole history of both of the ’FLs being dubious about a quarterback with a Canadian passport, with the CFL’s being worse since it has Canadian in the name. At least the CFL was earlier to embrace quarterbacks who are Black.

There are entire prognostication industries dedicated to the election, the College Football Playoff, and NFL Draft prospects of Kurtis Rourke.2 I am not here to cut their grass; Michigan State is the place to go if you want to learn how to cut grass. This was just about savouring and appreciating the people who help you have the experiences — a weak part of my IRL game — and wanting to share your football geekiness. Someone will want to read this, eh?

Through the binoculars, one could watch Rourke work. As the sun set behind the stands in the century-old bowl, he set up over and over, lightly bouncing on the balls of his feet, the slight turns, trained micro-movements, all radiated calmness behind firm pass protection.

Tip for football folklorists: keep one eye on reading the QB, and the other on the hand-to-hand stand-up combat in front of them. It takes you to the ball. Long ago, Joe Montana stated he read the colors. The NFL, even 40 years ago, moved too fast for a quarterback to individualize looming threats. If the San Francisco 49ers were in their home red, seeing the white tops of onrushing opponents triggered Montana’s flight impulses.3

You can take that and apply it to watching on screens, or in person. Depending on the direction the offense is trying to move, one eye is on the flesh-filled fray in the ‘tackle box,’ and the other is on seeing how the QB is reading and resetting. The talent level among receivers and the leagues’ desire for scoring and points means that when the QB throws a good ball, it will be a pass reception. Higher scores equal happy fans and fewer unhappy thoughts about whether the brain injury crisis will end the sport.

The traditional methods of telecasting football rely on an outdated binary. They were developed when a 50 percent competition percentage was the standard of efficiency. Nowadays, quarterbacks’ completion percentage is ignored. The standard is adjusted yards per attempt. It factors in touchdown passes and the disaster plays that come from a teamwide fray and a leaky offensive line: sacks and interceptions.

Indiana and Rourke had neither of those on Saturday. Once settled in, he only had to bolt the pocket once. Watching through the ‘binocs,’ one could get real-time own NFL Films tight-on-the-spiral view of a ball travelling to its target. That aerial game idyll might happen only a few times. But it is a sweet payoff, and it happened more than a few times in the second and third quarters when Indiana rang up 33 points at the north end.

That view might be coming to your area sports bar. The next big thing in off-site sports viewing is Cosm. It is a Shared Reality live sports and entertainment concept that will put a “live window format” in a shared space.4 It might be a climate-friendly solution, cutting down on the carbon footprint from people driving and flying to games, but that is another post.

The pointy ball zipping from Rourke’s “whip fast” right hand was an end function of all the mechanics the quarterback has built.5 In the spread game, the quarterback is the logistics officer routing passes and handoffs here, there, and everywhere to runners. It might not be stirring, but it can be relentlessly efficient, and from what I read, it’s what Indiana coach Curt Cignetti knows will work.

Is it convertible to the NFL? One scribe wrote it depends on whether an NFL team will give Rourke a chance. The NFL, aka Not For Long, is at an all-time nadir for rushing quarterbacks from first-round choice to draft bust. Rourke is actually 17 months older than Anthony Richardson of the Indianapolis Colts, who has already been benched.

For now, Indiana operates the way almost all top football teams move, and that fits well. The volume of run plays might exceed passes, but Rourke is lethally on-target. It’s the game that’s been developed through fusing the ‘CFL style’ into the American rules-game over the last 35 to 40 years.

A good dive into why football became ‘Throwball’ is S.C. Gwynne’s The Perfect Pass: American Genius and the Reinvention of Football (Scribner, 2016). It follows Air Raid offense originator Hal Mumme and, to some extent, the late great and better-known Mike Leach. They started developing their signature scheme at a small college in Iowa from 1989 till ’91 — a seminal period to start following football, concerning how it is played and followed in 2024.

Their brainstorm to go no-huddle came from watching a Don Matthews-coached run a practice drill called Bandit, meant to simulate a two-minute drill. Don Matthews, of course, is the greatest coach in the history of the Canadian Football League. So the drill taught by two football innovators came out of the CFL, full stop. Basically, the game you know and love on NFL Sundays and college Saturdays owes greatly to a ‘football lab’ in the apartment above the meth lab, with all apologies to Robin Williams.

Viewed one way — whelp, my way, the one everyone seems to tune out — Kurtis Rourke is right on time. A Canadian QB will have some underdog by definition. This underdog is 6-foot-5, 223 pounds, and a son of a family that could uproot to the football hotbed of Alabama when their firstborn son, Nathan Rourke, began to develop as a quarterback.6 As CBS Sports detailed, one Rourke breaking through the bias against Canadian quarterbacks meant the other could find acceptance. And material resources are necessary to be competitive in sports, regardless of what ’90s media imparted.

Kurtis Rourke may just be a rightontime player in an eras-spanning arc of how football has evolved, in the leagues in neighboring nations. Someone, i.e. not me, who has built a platform as a Football Knower needs to write a book about how the passing game philosophy of the NFL and U.S. college ball in 2024 is a direct descendant of the CFL style from the 1970s to ’90s when the little three-down league was inventive. ‘Playing Fast’ originated up here, in the days of Warren Moon in Edmonton, Condredge Holloway in Toronto, and then Doug Flutie at various stops.

I cannot be the author, since nearly no one sees me as a Football Knower. Reminders are on mental and emotional file. You didn’t play the game. You like the Minnesota Vikings. You like the CFL. You like stoopid Canadian college football. Well, thank you for the labels, but those labels are spurs to keep learning football over 3½ decades, watching it in copious amounts, learning it through books, through theorizin’ and folklorin’, and by ignoring TV talking heads. You are welcome, Enablers.

It feels like it is right on time for a Canadian to be among the passing leaders, when the Americans are playing a game that Americans, largely, worked out while exploring the space offered by Canadian football.

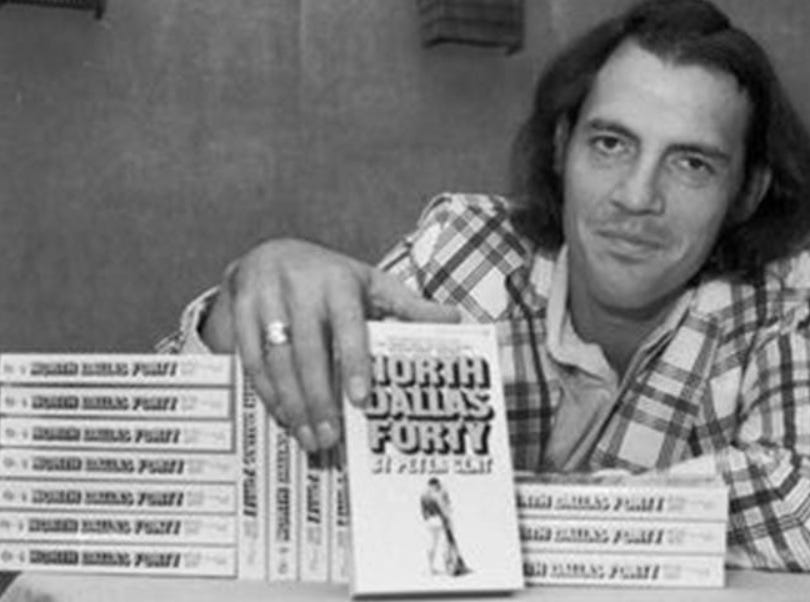

My immersion into the gridiron arts involved books by North Dallas Forty author Peter Gent (1942-2011), a Michigan State alumnus. The game of 2024 looks a lot like the one Gent described in 1980s fiction where “pass patterns changed in mid-route” and a team could “run its entire offense like a two-minute drill,” which put strange ideas in my head about what football could look like.7

Perhaps it comes down to whether you found football after your hockey immersion. Hockey is the fastest team game on earth, so it reckons that the Canadian gridiron game remained faster and freer-form and left in more the aggro and random elements in the third phase, the kicking/return games. Viewed from up here, it is a killjoy to want to play a static, closed system. Establishing the run is so passé, although yes, you do need a rushing game and a defence. The rules say so.

Anyway, it meshed well that my first game was at the alma mater of Peter Gent. For anyone still following along, it was a football game between basketball schools, at the alma mater of a favorite writer who got famous for writing about playing pro football, but did not play college football.

Peter Gent, the 1990s CFL, and the ‘chessboard gone mad’

Gent attained some storytelling fame in the 1970s and early ’80s since North Dallas Forty was a “tell-all novel (that) perfectly caught the spirit of the times.”8 The rub with physical media in my childhood was it might find its way to a sponge-brained sports geek. Around 1989 and ’90, his writing landed with a newly made teenager who knew that playing football was a non-starter since the nearest high school did not have a team.

And that might have been better anyway. Books, learned commentators, people who knew how to explain gently but firmly, offered more to a wannabe writer than trying to play ineptly. With Gent, I had an influencer, although it would be almost 20 years before I made a friend who had read his 600-page novel The Franchise (1983).

Gent, as a three-time Michigan State basketball scoring leader whom the Cowboys converted into a pass receiver, learned all of his football at the pro level. The novel focused on the business of football and a sinister side and also got out in front of how the sport would take a “quantum leap in revenue” by the 1990s. He also described a quarterback learning to play the field like a basketball court, distributing the ball quickly, simplifying the game down to geometry and angles.

This created simple terms for a teen who did not play. Getting the original 1988-vintage John Madden Football also helped with tinkering with formations seldom seen in the game of 1990. It encouraged believing there was Advanced football, the teams who played wide open, whether it was pass-happy or an option scheme. The attack had to be designed to win by outthinking people.

Gent’s alter ego in The Franchise is a quarterback named Taylor Rusk. His inspiring-confidence-in-the-huddle epitaph is: There’s no man in football who can outthink me. Because I just change my mind on the spot.

That was what I wanted to see.

Nineteen ninety was a transition period. The CFL offered the wide-open game where 80 to 85 percent of yards came through passing. Three downs, 12-a-side, unlimited motion for receivers was strategic wildfire. Around that time, there was loaded media skepticism about the Detroit Lions hiring Run ’n’ Shoot guru Mouse Davis. The old Sport magazine called it a “pantywaist offense without a tight end.” What the hell did that mean?

Akin to Kurtis Rourke having a door opened since his brother went ahead of him, the Houston Oilers installed it full-time in 1990. That season, Warren Moon, once snubbed, became the first NFL QB to have a 5,000-yard season that featured a 500-yard game.

The Run ’n’ Shoot’s sui generis was not the personnel. It was that every receiver could have five or six potential routes because, as Gent’s characters in his 1983 football novel described it, they “took their keys from the defenders after the snap.” This is now known as an option route, and they are in every football play.

Today, nostalgists probably know Davis demonstrated the Run ’n’ Shoot in the USFL, when he had Kelly with the USFL Houston Gamblers in the same market as Moon and the Oilers. The proof of concept before that was in the CFL with the Toronto Argonauts. A bit of memory burn was reading how Davis pointed out that with unlimited motion, he could “do things that were unstoppable.” Well, you can see the appeal of that to a sports nerd who felt bruised with rejection, usually in advance.

This all happened in a time delta where the NFL was guilty of ‘heightening’ with quarterbacks. Someone who was there has probably peered into, and pored over, why the NFL got so dogmatic that it spit out and rejected Doug Flutie in 1990. It was the era of the Prototype Pocket Passer — Dan Marino, John Elway, Kelly, Troy Aikman. — six-foot-four, ideally blond and blue-eyed with an arm the gods turned into a Thunderbolt, and free from any impulses to ditch the protective pocket that Paul Brown developed in the 1940s to protect quarterbacks.

That created a market inefficiency for the 1990s CFL. It is, as I have said to many people, the one football league that did have too many quarterbacks. It had such largesse it even tried putting CFL teams in the United States; really (well, that and the expansion fees). It was a haven for African-American quarterbacks, or those deemed too small or lacking a rocket arm, since the 65-yard-wide field allowed for more ‘touch’ passing.

And Flutie came to the CFL. Within a couple seasons, he was tossing the ball around so much for the Calgary Stampeders that the American media, during an era of “ugly football” in the NFL, could not help but notice. Sports Illustrated sent football scribe Paul Zimmerman (“Dr. Z”) to write about Flutie in the 1992 Grey Cup. (The era of ‘split run’ magazines might have been a factor.)

Zimmerman came away describing not a former Heisman Trophy winner and NFL reject lighting up lesser competition, but Flutie playing on “a chessboard gone mad,” as his receivers started plays with a sprint from 15, or 20 yards behind the line of scrimmage, and pass rushers came from all angles. The game, like the one that stirred this post was blip, with Calgary defeating Winnipeg by an NFL-like score, 24-10. The article afterward involved a seasoned writer, another Football Knower, who saw something and just wrote it.

In a game Flutie was born for—12 men on a side, no-back sets with as many as six receivers going out in patterns, blitzers pouring in like crazy, a chessboard gone mad—he was the master. He was a moving, darting exclamation point, scrambling to buy time, throwing the ball sidearm, underarm, once almost backhanded. (Sports Illustrated, Dec. 7, 1992)

Does that not sound exactly like how Patrick Mahomes has played since 2018? Wait, there is more.

The mighty NFL was challenged, rightly so, in the pages of the leading sports weekly when, you have heard this before, that meant something. The CFL was teetering financially, but Flutie told S.I. that parts of playing in the Canadian league were better. No comparisons; just complements. And the article, re-read 32 years later, portended how the NFL would change before the end of the 1990s.

“Going back to some closed-offense, ball-control team would be very boring. One year with New England I was averaging 15 throws a game at the end of the season. I was handing the ball off and watching the game. There was no such thing as mental fatigue.”

But what if, say, a run-and-shoot team became interested? John Hufnagel, the former Penn State quarterback who coaches the Calgary offense, says Flutie's best attribute is his ability to think on the go, to make the quick reads and adjustments. (S.I., Dec. 7, 1992)

What other quarterback pops to mind upon hearing quick reads and adjustments in the context of proving himself in an alternative league? Timeline-wise, two quarterbacks playing developmental football in 1992 have been retired from the NFL long enough to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

One, ah-duh, is Peyton Manning, who was then a high school junior in New Orleans and part of a Quarterback Dynasty. So, not him.

The other? You guessed it, Kurt Warner.

The Kurt Warner Arc is universally known — all-but-ignored prospect from a small school, lands in Arena Football, then suddenly leads the NFL’s Rams out of the football doldrums. In his biopic, American Underdog, it is played for derisive laughs when Warner, after joining the Rams, says the NFL moves slower than the Arena League. In reality, the Rams were mainstreaming what other leagues had done successfully to create their slews of space outside the NFL ecosystem.

There might well be no literal connection. There were NFL predecessors to the Greatest Show on Turf attack that Warner helmed from 1999-2001 as he became the greatest late bloomer in modern men’s pro sports history. The Rams looked like they were playing a CFL style — five potential receivers in the pattern, ball in the air in a blink. It drew raves and the Rams set records and snuck in one Super Bowl victory before central players aged and coaches frayed, and the Patriots dynasty got started.

Someone from a different form of football coming in and informing the NFL, you have faster and stronger individual players. Someone is processing the game at the same speed.

Those in the uber-American, four-down footballing stream had to play catch-up. They have overtaken it, thankfully. When the Americans get ahold of a great idea, they race to scale it up. Sometimes they forget to pump the brakes, and people get broken.

None of this was immediately self-evident watching an Indiana-Michigan State blowout on Nov. 2, 2024, three sleeps before The Election. The dots usually need a day to connect. The Election, for writerly purposes, is subtext.

It was just nice to be out at a football game and not think about bad-faith politics. And watch Canadian Kurtis Rourke spin it. Who knows?

Well, there is a theory

Athletes are sometimes made for a style that began to emerge at the time they popped into the world. Kurtis Rourke was born in late October 2000. His elder brother and Edmonton Elks QB Tre Ford were each born in 1998.

By then, the NFL had changed enough to re-welcome Doug Flutie and adapt concepts from the Run ’n’ Shoot. Its pure form was ill-suited to ball control. At levels below the NFL, it made sense to replace the bulky tight end and fullback with two diminutive dervishes who could run linebackers and safeties ragged. It indirectly invented the WR-Slot position that Spread offense teams use.

In the 2010s CFL, 5-foot-7, 150-pound Brandon Banks went from a punt return ace to a star slot receiver in that concept. The NFL needed players with its physical specs and the smarts and hands to play in it. Well, to extend that theory, Travis Kelce, who is listed as a tight end but really should be called a WR-Slot, was born in October 1989. And, yeah, Taylor Swift was born in 1989, too.

The point is, as far as this nerd was concerned, the NFL and U.S. college teams had to play catch-up to Canada. They are all caught up.

Wrapping up

Again, it would not do to try to outdo the full-timers, but Indiana is the story of the year in this unprecedented college football season. Thanks to commentators such as Shutdown Fullcast, and co-conspirators such as Homefield Apparel, 9-win Indiana was a meme that is seasons in the making. And it happened, and I got to see it, and feel happy for their fans!

The season is unprecedented since the Playoff has bumped out to 12 teams, and TV money-driven realignment turned the Power 5 conferences into a Power 4. And a Canadian quarterback is in the thick of it?

The college sports-literate know Indiana is a Basketball School — Hoosiers, for pity’s sake. A Basketball School plays football to unlock the entry door into a Power Conference, a pre-requisite for a high seed in the TV ratings-driven March Madness. It is possible to make the Final Four in men’s basketball without playing major college football; see Gonzaga, or Loyola of Chicago. Still, generally, basketball bluebloods such as Kansas, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, UCLA, Duke, North Carolina, Syracuse, and UCLA seem to fall into their place.

Indiana had not had a 9-win season in 57 years, which was so long ago that the Big Ten only allowed a team to play in the Rose Bowl, but never two seasons in a row. They have not sniffed around the top 10 in the wire-service poll since 1988.

Cignetti, as the media has written, used the transfer portal, college football’s provisional form of free agency, to load up seasoned ballplayers. That meant bringing in Rourke, a ‘sixth-year senior’ by way of the Ohio Bobcats, where he backed up his brother his first couple of years.

What do Rourke and Indiana look like through binoculars and eyes belonging to someone delulu enough to think he can offer insight from the 30th row? Forget stats. Forget rankings. It just looks unfair to mid-level to lower-placed Big Ten opposition when Indiana and Rourke are rolling on offense and their defense-special teams are quickly regaining possession and generating field position. Saturday was the first time the Hoosiers trailed all season, almost as if they liked a challenge.

By the end of the third quarter, they were up by three touchdowns and change. There was no obvious explosion plays by Rourke’s side, just repeated precision strikes. The colour in front of him, to think of Montana’s rule from the beginning of this, pretty much stayed in the away team’s whites.

Set up, shift the body, tight spiral, on target, on time. There was not too much on offer from Michigan State’s football team. Once a halftime karaoke party led by the MSU marching band was over, the stadium was deforested, almost all the Spartans green emptying out and leaving Hoosiers’ red.

The point of this is it was a privilege to see him play — and a nice bonus that he validated heartfelt football beliefs. He was playing the kind of football that was foretold during my immersion, although Pete Gent might not have liked his old school taking a beatdown.

Code-switching from three-down to four-down football has always been seamless. Not everyone feels that way. The point of it is to put football in a personal continuum. Smaller products always come up with something that the bigger, behemothic competitor studies and uses well.

Put that in a book, someone, please. Perhaps it will have to hang on Kurtis Rourke cashing the lottery ticket and becoming a long-term, established starter in the NFL. It felt like pieces coming into place, and if not, well, it was plenty enjoyable. Savour Football Saturdays when you have ’em.

Nov. 2-4, 2024

East Lansing, Mich.; Windsor / Hamilton, Ont.

Rourke is the No. 2-rated passer in the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision, between Jaxson Dart of Mississippi and Will Howard of Ohio State.

See Rob Staton, “My thoughts on Indiana quarterback Kurtis Rourke,” Seahawks Draft Blog, Oct. 24.

Joe Montana, Bob Raissman, “Audibles: My Life in Football,” first published Jan. 1, 1986.

See Candice Williams, “Cosm entertainment venue coming to Bedrock's Development at Cadillac Square,” Detroit News, Nov. 1.

See Brandon Marcello, “How Indiana QB Kurtis Rourke rose from Canadian underdog to force behind Hoosiers' dramatic turnaround,” CBS Sports, Oct. 17.

Marcello, CBS Sports, Oct. 17.

Gent expressed those notions in his novel The Franchise (1983), which I read in late 1989.

Anon., “Peter Gent (1942–2011) – a Fine Writer Who Happened to Play Pro Football,” mobilemojoman, Oct. 20, 2011.