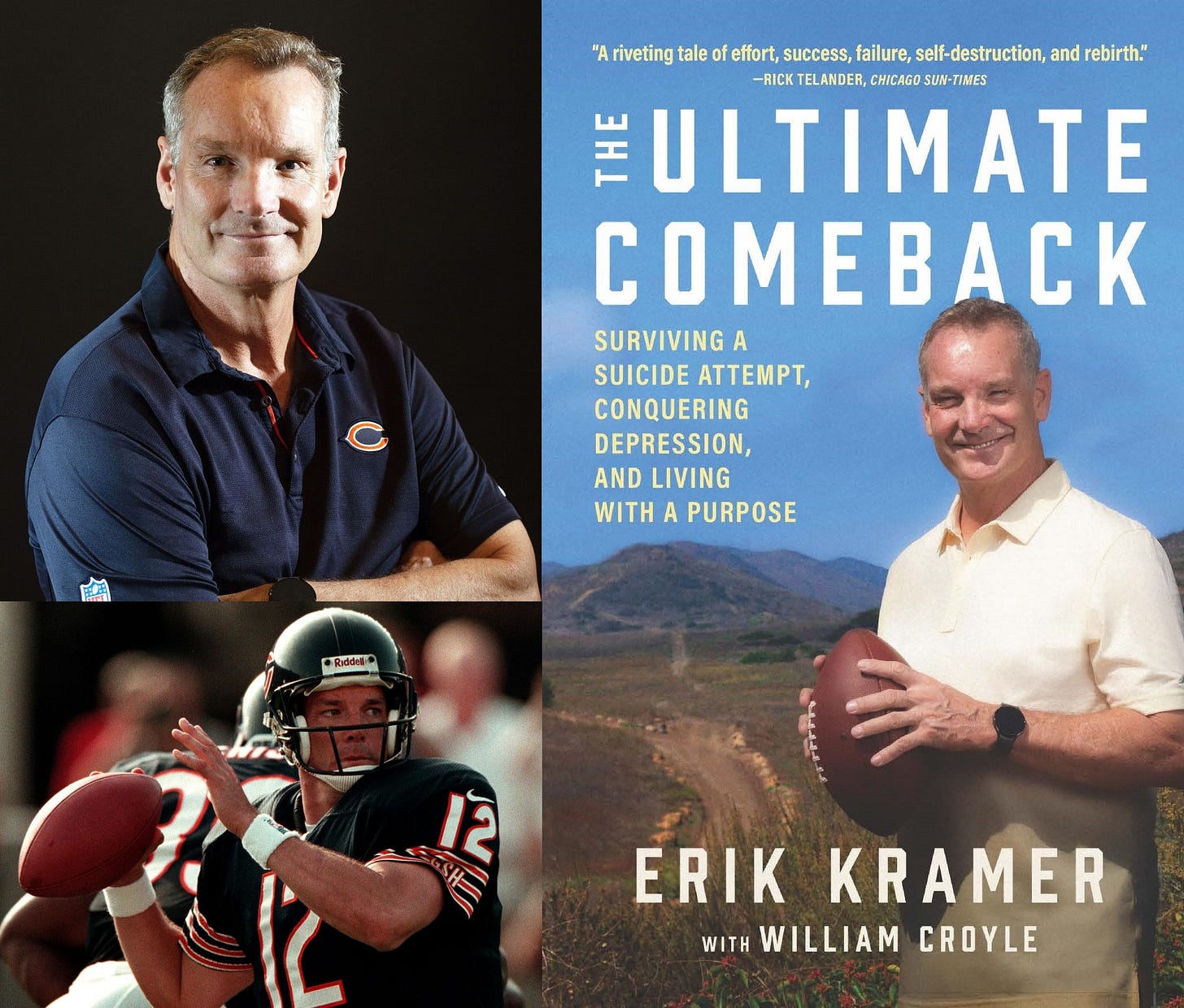

Erik Kramer, "The Ultimate Comeback" — SportsLit S8E01

The 1990s-era NFL quarterback talks about surviving a suicide attempt, moving on from the death of a child, and good habits that become "the glove that all of those fingers fit into."

Content warning: suicide, depression, drug poisoning.

One of the screening questions you get asked after contacting a distress line is whether you have a suicide plan. Erik Kramer, the quarterback turned mental health advocate, made a very meticulous one in 2015, as he and his collaborator William Croyle describe in The Ultimate Comeback: Surviving a Suicide Attempt, Conquering Depression, and Living with a Purpose (Whitsett Avenue Publishing, November 2023).

The leadoff guest for SportsLit in 2024 is an open book about his routes to and from his lowest point. Eight years ago, Kramer survived shooting himself under the chin in a Southern California hotel room. The timing for sharing his message is opportune due to the success of one of his former teams. Kramer, whose brain chemistry once had him convinced he should not be alive, was the only living American who had quarterbacked the Detroit Lions to an NFL playoffs victory. That distinction changed the literal day before he gave plenty of time Neil Acharya and me.

“The reaction has been visceral,” Kramer says. “It’s not a depressing book. It’s an all-encompassing look at someone’s life that people will find something in which they relate.”

Negative feelings that are symptomatic of the genetic markers for depression and social anxiety start to show up in the preteen years. It was great to hear that Kramer is intent on developing workshop programs with children about good mental health habits, having a “home team,” and the fun of football.

Introduction

1:40. Erik Kramer shows up on some 1990s NFL leaderboards. In 1995, for instance, he was the No. 4-rated passer in the league, ahead of hall of famers Steve Young, Dan Marino, and Warren Moon. That was very heady for an athlete who played defensive back, not quarterback, as a high school senior, then took the California junior college route — shades of Last Chance U! — to earn a major-conference opportunity at North Carolina State. And he was passed over during the 12-round NFL draft in 1987 after a conference player-of-the-year campaign.

5:15. From 2012, the Thousand Oaks Acorn has a summary of the criminal trial that stemmed from the drug overdose death of Kramer’s first-born son, Griffen Kramer. Erik Kramer survived his suicide attempt just under four years later.

5:45. Dan Wetzel and Tyler Dunne have done yeoman’s work chronicling the horrifying aftermath Kramer faced during his recovery. The injuries from shooting himself left Kramer with a vastly reduced reasoning capacity. In a case of dependant-adult abuse, a former girlfriend re-inserted herself into his life and stole a high five-figure sum of Kramer’s life savings. Dunne and Kramer also conversed last month on the Go Long podcast.

7:15. There are some surface-level similarities in the career arcs of Kramer and Kurt Warner, beyond having 10 letters in their names and a K where you might expect a C.

Both toiled in alternative leagues. Warner played arena football and was assigned to NFL Europe, the spring developmental league. Kramer, after getting thrown into action in a strike season, also had a turn up north with the Calgary Stampeders before a cold call to the Detroit Lions led to an opportunity.

Both landed with moribund Midwestern teams that were desperate enough to be different. Warner was the linchpin in the St. Louis Rams’ Greatest Show on Turf offense, which set league records on the way to a Super Bowl title in the 1999-2000 season and a second appearance two seasons later. Kramer joined the Detroit Lions when the organization had brought in run-and-shoot gurus Mouse Davis and June Jones as offensive coaches. The run-and-shoot, which replaced the tight end and fullback with two smaller, slippery slot receivers, was perhaps ill-suited to sustained NFL success. But

Both needed the starter to go down to get their opportunity. The Greatest Show on Turf was initially supposed to feature Trent Green. Green was lost for the year before the regular season, and Warner, who had played all of two minutes 38 seconds in the NFL, stepped right in.

Similarly, Kramer with Detroit was probably supposed to be the No. 3 quarterback behind starter Rodney Peete, and first-round choice Andre Ware. But Kramer beat out Ware for the backup role and stepped in when Peete was injured in 1991. Detroit went on to a 12-win regular season and a trip to the NFC Championship Game. It, of course, has taken the Lions 32 seasons to repeat those feats.

9:00. To the point about Kramer making quick decisions, he ranks as one of the 25 hardest-to-sack quarterbacks in the history of the NFL. His sack percentage of 5.04 is 24th-best all-time.

10:00. I got a bit rambly and riffy in this passage, which was an attempt to describe how the preferred style of quarterback play in the NFL went from, say, Dan Marino to the touch and feel of Mahomes.

The NFL style of offence in the ’20s looks like the Canadian Football League in the 1990s. Lots of motion and aggressiveness, with QBs who are adaptive and possess arm talent and touch.

Thirty-five to 40 years ago, the NFL was in thrall with the P3 QB — the Prototype Pocket Passer. That was the old school’s reaction to scoring-friendly rule changes.

In 1978, while Marino, John Elway, and Jim Kelly were all seniors in high school, the NFL changed a series of rules. For instance, it limited bump-and-run coverage by defensive backs largely on account of one cornerback. Mel Blount of the Pittsburgh Steelers was absurdly effective at taking out a receiver.

So, NFL teams would start passing more. You needed someone reliable if you were going to have to try 30 passes a game. So QB1 should be six-foot-four, white, and move Crash Davis to say, “When you were a baby, the Gods reached down and turned your right arm into a thunderbolt.”

Elway, Kelly, and Marino were among the six QBs taken in the first round in the famous Quarterback Draft in 1983. All six were listed at 6-foot-3 or 6-4. And all six were white.

A quarterback from either the ’83 or ’84 draft class started for the AFC rep in 10 Super Bowl contests in a row (1984-93). And their teams went 0-10.1 There was some loss of acknowledgment that the quarterback needed to be an adaptive athlete who could get the ball out quickly. That was what I was trying to say. Dan Marino was elite because of how quickly a football came out of his hand. He might have been just as elite if he was 6-foot-2.

Either way, teams eventually remembered it was about well-harnessed skill and the will to win, rather than checking boxes on a scouting form. In the long run, hand measurement matters more with a quarterback prospect than whether he is 6-5 or 5-11¾.

Here are some follow-along notes that add context to people, places, and things referred to in the conversation with Kramer. Erik and his spouse Anna Dergan have our gratitude for their generosity and time.

Interview

21:30. In discussing collaborator William Croyle, Kramer mentions the memoir by Genelle Guzman McMillan, Angel in the Rubble: The Miraculous Rescue of 9/11’s Last Survivor. Guzman McMillan survived 27 hours before she was found.

25:30. “Nothing mattered until he became the glove that all of those fingers fit into.” In the chapters of the book about his Detroit Lions years, Kramer worked with sports psychologist Dr. Kevin Wildenhaus.

At times, engaging a sports psychologist or a mental coach was hush-hush or taboo. Things have changed. A report from ESPN’s Holly Rowe on Michigan Wolverines QB J.J. McCarthy during the College Football Playoff championship game on Jan. 8 prompted that question.

34:00. “Forgiveness is what’s given … it’s a way of washing yourself from the burden.” The question here was prompted by reading that article from 2012 where Kramer expressed forgiveness to the young adult who injected heroin into Griffen Kramer, causing his death.

38:00. One of the book’s more uplifting themes is that Kramer seems to have had better parental relationships with his dad and mum (who both died in the early 2010s) as an adult than as a child. In the narrative, his father comes across as an Overinvolved Sports Dad. His mother was hypercompetitive and seemed to lack a “maternal component.” But Kramer writes that “when she sensed my depression in the mid-1990s, Mom revealed her unconditional love for me, and our relationship grew from there, but it was a long road for both of us.”2

44:40. Kramer played with Calgary late in the 1988 CFL campaign.

When he mentioned throwing six interceptions in one game, I wanted to interject and point out that Doug Flutie once threw six picks during a Stampeders-Edmonton Labour Day game. You have to be good if the coaching staff lets you throw that many INTs.

Kramer mentions Tim Petros (1961-2020), a running back for the Stampeders. The reason I knew about Petros holding the Vanier Cup rushing record was because his Calgary Dinos team defeated the Queen’s Golden Gaels for the Canadian university crown in 1983. Queen’s exacted payback 26 seasons later.

49:00. In this section, I wanted to hear a former quarterback’s insight into how the passing-game concepts in the run-and-shoot were absorbed into the bloodstream of NFL schemers.

As Kramer notes, the run-and-shoot was made for the levels of football with wider hash marks. As someone who never played gridiron football, that had not occurred to me, but I can extrapolate based on my knowledge of the four codes of throwball (NFL, NCAA, CFL, Canadian amateur).

Davis developed the system in U.S. high schools, where the hashes are 53’4” from the respective boundaries. That used to be the distance in the NCAA before it was moved to 60 feet from the sidelines in the early 1990s. The NFL keeps the play more in the middle of the field. Its hash marks are 70’9” from each boundary.

Davis also brought the run-and-shoot to Canada with the Toronto Argonauts. The CFL hash marks were 24 yards from the near sideline, creating a 41-yard wide side — four-fifths the width of an American gridiron. That’s too much, man, to play man-to-man.3

At the NFL level, where the talent is spread fairly equally across all teams and all positions compared to the NCAA and amateur age-group leagues, it eventually became difficult to be balanced and efficient. The pure form of the run-and-shoot was too radical. It left the quarterback unduly exposed physically. They went under centre to take the snap, instead of going in the shotgun set, and often threw after rolling out. Their offensive line did not get blocking help from a fullback, H-back, or tight end, since they were replaced with slot receivers.

The Houston Oilers and Warren Moon, who would go in the shotgun, put up big numbers using the run-and-shoot in the 1990s. But their infamous playoff collapse against the Buffalo Bills — the 35-3 game — fed into confirmation bias that the offence was ill-suited to the mighty NFL.

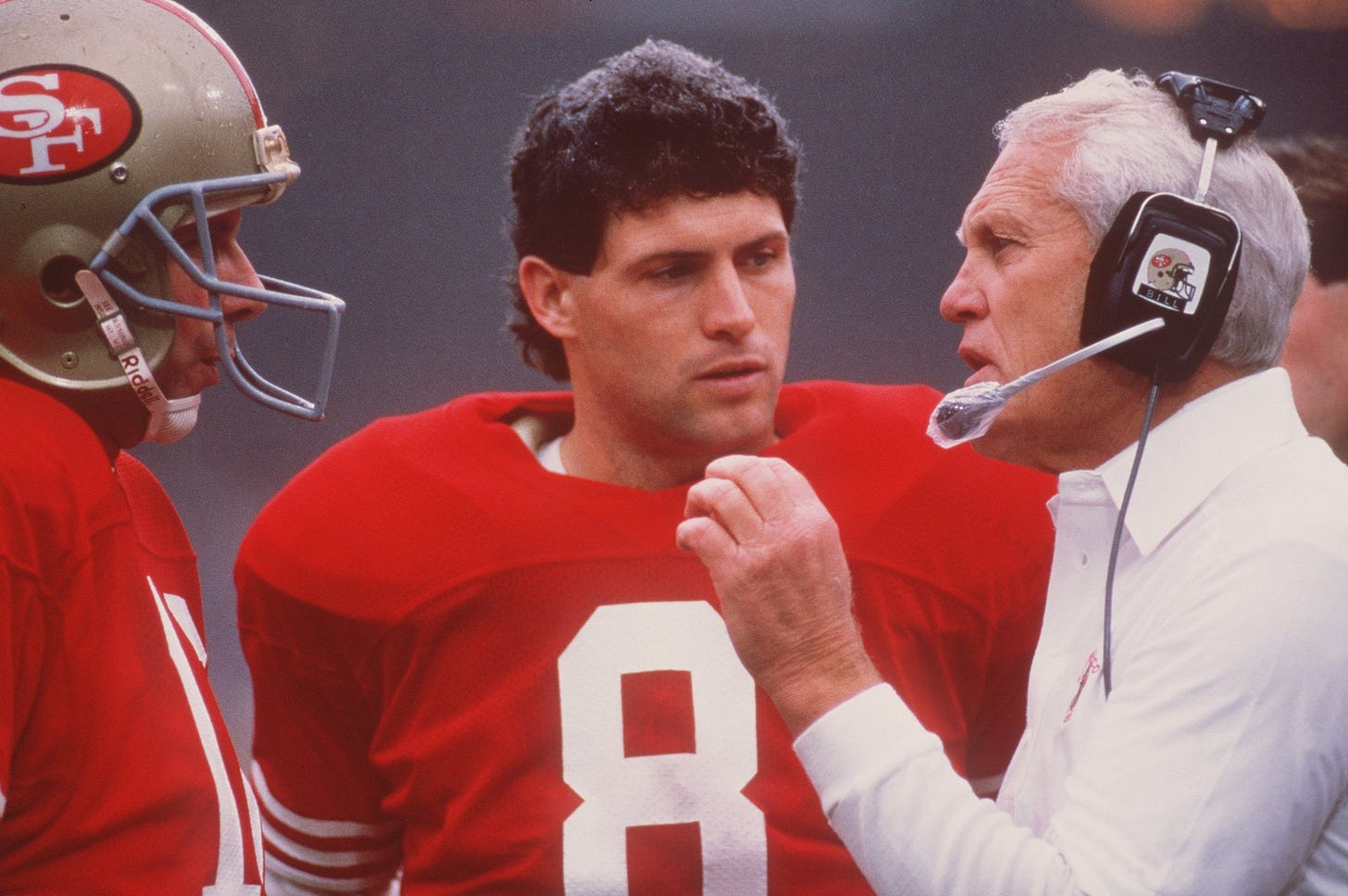

And as Kramer points out, the West Coast offence that Bill Walsh developed in the 1970s and ’80s was most influential. Like anything, necessity was the mother of invention. This is where Nerd Neate well-ackshullys that Walsh created his scheme with the Cincinnati Bengals a decade or so before the start of the San Francisco 49ers dynasty (1981-1997).

Walsh, in 1970 and ’71 with the Bengals, was reliant on a quarterback named Virgil Carter whose “throwing range was roughly 15 yards in any one direction.”4 The Bengals were also a young team moving from the AFL into the NFL. So Walsh built a system around short passes and the Bengals scored a coup by winning their division in their first NFL season. Carter, noodle arm and all, also led the NFL in completion percentage the following season.5

Another Walsh charge, Ken Anderson, had a long, borderline hall-of-fame career with Cincinnati and became the first NFL quarterback to complete 70 percent of his passes in a season. But by then Cincinnati had lost one Super Bowl to the San Francisco 49ers and the Walsh-Joe Montana coach-QB combo.

Evolution is undefeated, though. The concepts are still in the game, and now teams have receivers with tight end dimensions and a run-and-shoot slot receiver’s guile.

54:15. Kramer was with the Lions when they won the NFC Central division in 1993, but lost a wild-card round game against the Green Bay Packers and a young Brett Favre.6 After becoming a free agent, Kramer played for the Chicago Bears from 1994 till ’98, and had a final season with the San Diego Chargers.

57:30. Neil alludes to with the Bears is the franchise’s struggle to find a generational quarterback. They have not had much luck, man, since Sid Luckman retired 73 seasons ago. Go look up Sid Luckman in another tab. He was great. He has been dead a quarter-century, and his spirit still makes me want to go slam into a cement wall.

Kramer brought the chat around to the current lay of the football landscape in Chicago. General manager Ryan Poles and the front office have the No. 1 overall choice. They have the first call on the consensus best quarterback, Caleb Williams from the USC Trojans. But a franchise riding five no-playoffs seasons in a row needs help everywhere.

Defences don’t win championships in football. Lines win championships, especially the O-line in front of a very good-to-great quarterback. So it is understandable why the Bears, or their fans, would desire a trade for a premiere offensive tackle and/or pass rusher, while also getting their quarterback.

1:01:30. “There’s a lot to be said for a coach who can lead people.” In 1999, when Ryan Leaf suffered a season-ending injury in a minicamp, the Chargers went with 36-year-old Jim Harbaugh and 35-year-old Kramer as their quarterbacks. Since Harbaugh just guided Michigan to an undefeated, undisputed championship season in college football, I had to ask Kramer about having Harbaugh as a teammate. Of course, the quarterbacks on a team are also competitors, so that made for some interesting feedback.

Since the convo with Kramer, of course, Harbaugh has moved to the Los Angeles Chargers. It is paywalled, but Holly Anderson and Spencer Hall penned an excellent take (“To The Victor”) about Harbaugh. And, of course, Harbaugh had a hilarious cameo on Detroiters, Tim Robinson’s first comedy series.

Anyway, here is hoping this made for good reading to complement a good listen. SportsLit shall have another new episode dropping early this week. Enjoy the AFC and NFC title games if you are planning to follow.

That is enough for now. Please stay safe, and be kind — especially to yourself.

Boomer Esiason entered the league through the 1984 draft. Esiason was 6-foot-4, but lefthanded. His Cincinnati Bengals team reached the Super Bowl at the end of the 1988 season, losing to 6-foot-2 Joe Montana and the San Francisco 49ers.

The Denver Broncos lost three Super Bowls in four seasons from the 1986 to ’89 seasons. They won back-to-back in 1997 and ’98, allowing Elway to go out on top.

The Ultimate Comeback, pgs. 17-18.

In 2022, the CFL in its infinite wisdom moved the hash marks to 28 yards from the sideline — as in, hey, let’s make our alternative product look more like the more popular and better funded American version. The Canadian amateur rulebook still has them 24 yards in.

“Carter’s Short Passes Provided Pattern for Walsh’s 49er Success.” Jack Shepard, Los Angeles Times, Aug. 31, 1985.

Take away 1971, and Carter was a 51% career passer.

From 1970 till 2001, the NFL had three divisions in each conference: Central, East, and West. Chicago, Detroit, Green Bay, and the Minnesota Vikings comprised the Central, with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers thrown in starting in 1977.

In 2002, the addition of the Houston Texans enabled the creation of the current eight-division alignment with an East, North, South, and West in each conference.